This is part of the “Compiling Black with mypyc” series.

- Pt. 1 - Initial Steps

- Pt. 2 - Optimization (you’re reading this one)

- Pt. 3 - Deployment

Optimizing for mypyc

Having compiled Black successfully without it blowing up, it was time to try to optimize Black for mypyc. While mypyc is designed to handle all sorts of statically typed code, changing up the code even a little bit can allow mypyc to perform additional optimizations, ultimately helping performance a bunch.

And while I did go into this hoping I could spot some potential architectural or data structure optimizations, I wasn’t able to so the optimizations shared will be mypyc specific.

Getting started

First off, profiling! It’s hard to optimize code well if you don’t know where time is being spent.

To start off, I profiled Black over some of its own source code with cProfile to get a birds eye view:

$ python -m cProfile -o profile.pstats -m black src/black/__init__.py --check

All done! ✨ 🍰 ✨

1 file would be left unchanged.

$ gprof2dot profile.pstats | dot -Tsvg -o profile.svg

With the help of gprof2dot (well, actually the yelp-gprof2dot fork), I converted the profiling data into a nice SVG graph which I could then open in my web browser.

Tip: please open this massive SVG in a new tab because viewing it here will probably be painful :)

I tried using Scalene as I’ve heard good things about it, but it didn’t work sadly. It wasn’t that bad as I still had py-spy, line_profiler, and good ol’ cProfile. py-spy in particular was invaluable since it can profile (well err sample) C extensions which cProfile cannot. line_profiler was used exclusively for micro-optimizations :p

Anyway, I repeated this process quite a few times, making sure to try different files to get a general feel where time is going regardless of the input. Here are the main takeaways:

Initial parsing with blib2to3 takes up 30-50% of formatting runtime!

The AST equivalent safety check is cheap at 5-10% (obviously only when changes were made, otherwise it’s zero 🙂)

The actual formatting logic’s runtime is mostly spent in the CST visitor usually taking up 75%. The rest went to the transformers which handle line breaks, string literals, and some special cases.

I was quite surprised how much time blib2to3 related functions were eating up. Just look how concentrated the hotspots really are!

These hotspots make this part of the codebase way easier to optimize, so I optimized blib2to3 first.

It’s been so long since I first looked into this, so I don’t remember what optimizations I tried initially, but I do remember them having no effect :(

I tried other things and they actually helped 🎉 … probably since I took into account how mypyc works. Ultimately, many different optimizations were done over three rounds.

Tightening up existing type annotations

The stricter the type annotations are in your codebase, the more invariants mypyc will be able to infer. It’ll then use this information to write type-specific code that is faster. This code won’t work if it gets an object of a different type, but that’s why we use and enforce type annotations, so mypyc can safely assume it’s going to be the right type. In essence, the stricter the type annotations, the faster code mypyc can generate.

This meant reading through the code’s control flow, checking whether certain states are impossible. Blib2to3 is a legacy codebase, so type annotations were added to unblock other work. The goal was to make blib2to3 type check, and not write perfectly typed code. So naturally, there were a few permissive (parameter) type annotations I could make stricter:

diff --git a/src/blib2to3/pgen2/parse.py b/src/blib2to3/pgen2/parse.py

index 47c8f02..6b03188 100644

--- a/src/blib2to3/pgen2/parse.py

+++ b/src/blib2to3/pgen2/parse.py

@@ -138,7 +138,7 @@ class Parser(object):

self.rootnode: Optional[NL] = None

self.used_names: Set[str] = set()

- def addtoken(self, type: int, value: Optional[Text], context: Context) -> bool:

+ def addtoken(self, type: int, value: Text, context: Context) -> bool:

"""Add a token; return True iff this is the end of the program."""

# Map from token to label

ilabel = self.classify(type, value, context)

@@ -185,11 +185,10 @@ class Parser(object):

# No success finding a transition

raise ParseError("bad input", type, value, context)

- def classify(self, type: int, value: Optional[Text], context: Context) -> int:

+ def classify(self, type: int, value: Text, context: Context) -> int:

"""Turn a token into a label. (Internal)"""

if type == token.NAME:

# Keep a listing of all used names

- assert value is not None

self.used_names.add(value)

# Check for reserved words

ilabel = self.grammar.keywords.get(value)

@@ -201,12 +200,10 @@ class Parser(object):

return ilabel

def shift(

- self, type: int, value: Optional[Text], newstate: int, context: Context

+ self, type: int, value: Text, newstate: int, context: Context

) -> None:

"""Shift a token. (Internal)"""

dfa, state, node = self.stack[-1]

- assert value is not None

- assert context is not None

rawnode: RawNode = (type, value, context, None)

newnode = self.convert(self.grammar, rawnode)

if newnode is not None:

Since mypyc injects runtime type checks, simplifying Optional[Text] to Text reduces

function call overhead. value only needs to pass (in equivalent C code)

isinstance(value, str). This also has the neat side-effect of allowing me to remove some

asserts.

Tightening up type annotations involving typing.Any can be particularly

worthwhile as it forces the use of generic C code that can handle any kind of object. I

could only make this change once, but it’s better than nothing.

@@ -54,14 +56,14 @@ class Driver(object):

self.logger = logger

self.convert = convert

- def parse_tokens(self, tokens: Iterable[Any], debug: bool = False) -> NL:

+ def parse_tokens(self, tokens: Iterable[GoodTokenInfo], debug: bool = False) -> NL:

"""Parse a series of tokens and return the syntax tree."""

# XXX Move the prefix computation into a wrapper around tokenize.

p = parse.Parser(self.grammar, self.convert)

p.setup()

lineno = 1

column = 0

Marking everything Final

Avoiding calculating the same value over and over again is one of the most common

optimizations out there, and it’s for good reason, it’s usually easy to fix. BUT, with

mypyc we can take this further by using typing.Final. Final variables

can often be injected at lookup sites at compile time, skipping the lookups at runtime!

Let me show an example, let’s take this code and see what adding a single Final does.

SCALE = 5

def calculate_y(x):

return x * SCALE

Compiling it with mypyc, the C code for the calculate_y function is .. well .. quite

long! Notice how much work has to be done to safely look up the global value at runtime.

| |

If we mark the SCALE variable as Final, mypyc will notice that and inline the value.

from typing import Final

SCALE: Final = 5

def calculate_y(x):

return x * SCALE

Just look at how much shorter this is!

| |

If the value can’t be inlined, say because it involves a function call then mypyc will just replace the globals dictionary lookup and instead use a C static (which is still faster).

Applying this optimization to Black yields changes like the following to black.comments

and black.parsing1 respectively:

@@ -12,11 +18,10 @@ from black.nodes import STANDALONE_COMMENT, WHITESPACE

# types

LN = Union[Leaf, Node]

-

-FMT_OFF = {"# fmt: off", "# fmt:off", "# yapf: disable"}

-FMT_SKIP = {"# fmt: skip", "# fmt:skip"}

-FMT_PASS = {*FMT_OFF, *FMT_SKIP}

-FMT_ON = {"# fmt: on", "# fmt:on", "# yapf: enable"}

+FMT_OFF: Final = {"# fmt: off", "# fmt:off", "# yapf: disable"}

+FMT_SKIP: Final = {"# fmt: skip", "# fmt:skip"}

+FMT_PASS: Final = {*FMT_OFF, *FMT_SKIP}

+FMT_ON: Final = {"# fmt: on", "# fmt:on", "# yapf: enable"}

@dataclass

@@ -36,6 +36,11 @@ except ImportError:

else:

ast3 = ast27 = ast

+if sys.version_info >= (3, 8):

+ TYPE_IGNORE_CLASSES: Final = (ast3.TypeIgnore, ast27.TypeIgnore, ast.TypeIgnore)

+else:

+ TYPE_IGNORE_CLASSES: Final = (ast3.TypeIgnore, ast27.TypeIgnore)

+

class InvalidInput(ValueError):

"""Raised when input source code fails all parse attempts."""

@@ -160,10 +165,7 @@ def stringify_ast(

for field in sorted(node._fields): # noqa: F402

# TypeIgnore has only one field 'lineno' which breaks this comparison

- type_ignore_classes: Tuple[Type, ...] = (ast3.TypeIgnore, ast27.TypeIgnore)

- if sys.version_info >= (3, 8):

- type_ignore_classes += (ast.TypeIgnore,)

- if isinstance(node, type_ignore_classes):

+ if isinstance(node, TYPE_IGNORE_CLASSES):

break

try:

In total, this was the most common optimization I applied throughout this whole project. It’s simple but effective!

Taking advantage of early binding

Final is so fast because of early binding. What’s great is you can take advantage of

early binding with function calls too, assuming your code is static enough.

Time for another example:

from typing import Callable, List

def tag(item: object) -> str:

return "<tag>" + repr(item)

def process_items(func: Callable[[object], object], items: List[object]) -> List[object]:

return [func(i) for i in items]

process_items(tag, ["1", "2", "3"])

The function used to process the items isn’t known until call time, forcing mypyc to fall

back to the standard Python calling convention (albeit it does use the faster

vectorcall convention available for C functions). If I instead hardcode tag in

process_items, mypyc can call the C function directly which involves way less work.

from typing import List

def tag(item: object) -> str:

return "<tag>" + repr(item)

def process_items(List[object]) -> List[object]:

return [tag(i) for i in items]

process_items(["1", "2", "3"])

CPyL3: ;

cpy_r_r8 = CPyList_GetItemUnsafe(cpy_r_items, cpy_r_r3);

cpy_r_i = cpy_r_r8;

- PyObject *cpy_r_r9[1] = {cpy_r_i};

- cpy_r_r10 = (PyObject **)&cpy_r_r9;

- cpy_r_r11 = _PyObject_Vectorcall(cpy_r_func, cpy_r_r10, 1, 0);

- if (unlikely(cpy_r_r11 == NULL)) {

+ cpy_r_r9 = CPyDef_convert(cpy_r_i);

+ CPy_DECREF(cpy_r_i);

+ if (unlikely(cpy_r_r9 == NULL)) {

CPy_AddTraceback("early_binding.py", "process_items", 7, CPyStatic_globals);

goto CPyL8;

}

Most of the time this isn’t possible because if your function calls are dynamic, it’s probably because the code depends on it … but keep it in mind.

By sheer luck, I was able to replace two dynamic function calls with static calls in

blib2to3.pgen2.parse.Parser, the very hot parser code!

diff --git a/src/blib2to3/pgen2/parse.py b/src/blib2to3/pgen2/parse.py

index 6b03188..b5da4fa 100644

--- a/src/blib2to3/pgen2/parse.py

+++ b/src/blib2to3/pgen2/parse.py

@@ -23,7 +23,7 @@ from typing import (

Set,

)

from blib2to3.pgen2.grammar import Grammar

-from blib2to3.pytree import NL, Context, RawNode, Leaf, Node

+from blib2to3.pytree import convert, NL, Context, RawNode, Leaf, Node

@@ -199,16 +206,13 @@ class Parser(object):

raise ParseError("bad token", type, value, context)

return ilabel

def shift(self, type: int, value: Text, newstate: int, context: Context) -> None:

"""Shift a token. (Internal)"""

dfa, state, node = self.stack[-1]

rawnode: RawNode = (type, value, context, None)

- newnode = self.convert(self.grammar, rawnode)

- if newnode is not None:

- assert node[-1] is not None

- node[-1].append(newnode)

+ newnode = convert(self.grammar, rawnode)

+ assert node[-1] is not None

+ node[-1].append(newnode)

self.stack[-1] = (dfa, newstate, node)

def push(self, type: int, newdfa: DFAS, newstate: int, context: Context) -> None:

@@ -221,12 +225,11 @@ class Parser(object):

def pop(self) -> None:

"""Pop a nonterminal. (Internal)"""

popdfa, popstate, popnode = self.stack.pop()

- newnode = self.convert(self.grammar, popnode)

- if newnode is not None:

- if self.stack:

- dfa, state, node = self.stack[-1]

- assert node[-1] is not None

- node[-1].append(newnode)

- else:

- self.rootnode = newnode

- self.rootnode.used_names = self.used_names

+ newnode = convert(self.grammar, popnode)

+ if self.stack:

+ dfa, state, node = self.stack[-1]

+ assert node[-1] is not None

+ node[-1].append(newnode)

+ else:

+ self.rootnode = newnode

+ self.rootnode.used_names = self.used_names

Also since blib2to3.pytree.convert is guaranteed to return a non-None value, I could

drop a branch which was neat :)

Detour: let’s build developer tooling!

If you’ve worked with me before you’ll know that I love to write developer tooling to make life easier. (Un)fortunately this project needed two bits of tooling that simply didn’t exist at the time:

- A benchmark suite

- A tool to compare two builds of Black behaviourally

The first one is pretty self-explanatory, I needed a good benchmark suite to make sure this project would actually improve performance, and to also quantify the gains (important when weighing optimizations).

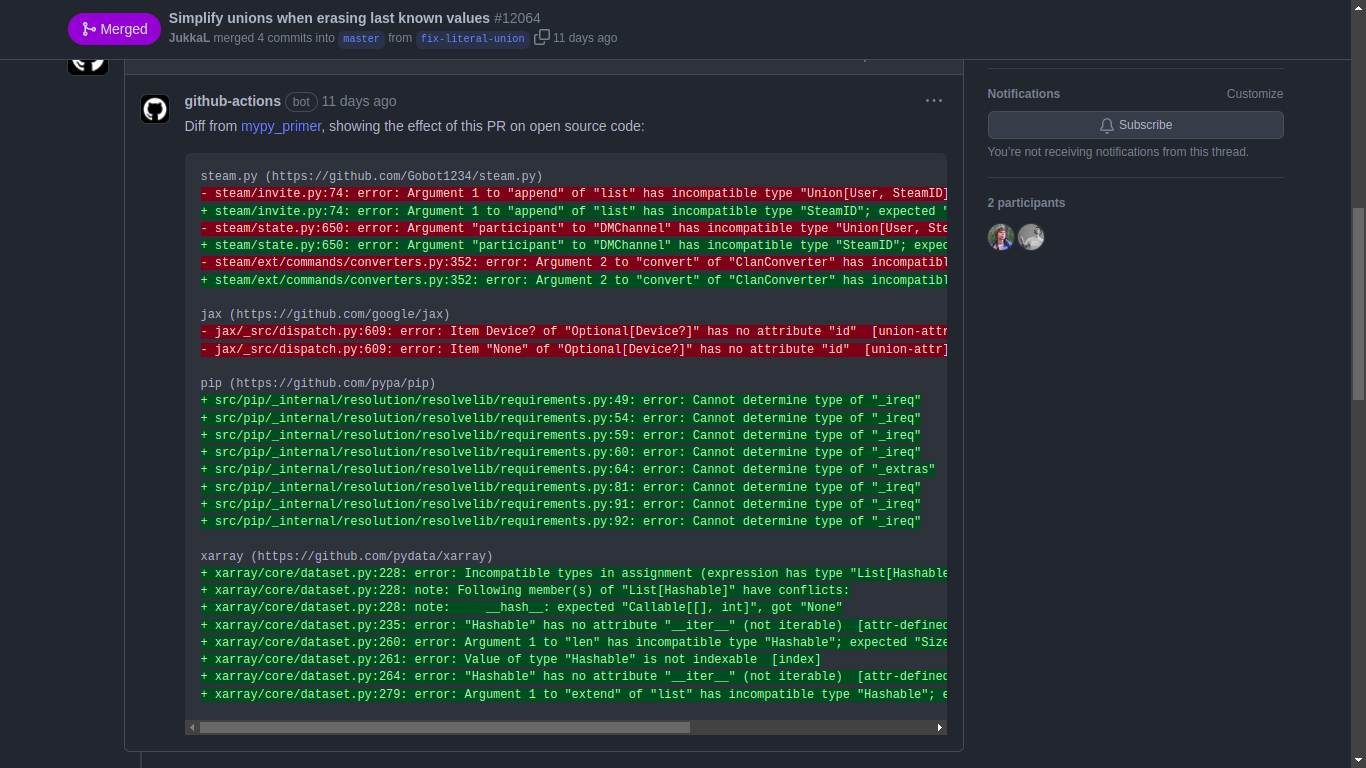

The second one is less clear, I effectively wanted mypy-primer, but for Black:

So I got to work creating blackbench and (the original) diff-shades. In hindsight, blackbench sucks and needs a rewrite so I don’t want to go into too much detail about it, but the summary is that it came with benchmarks for the following tasks:

- Formatting with safety checks

- Formatting without safety checks

- Blib2to3 parsing

across quite a few inputs. The story is similar for the original diff-shades, it worked and made it possible to verify mypyc didn’t change formatting, but its code was horrible (and not to mention unmaintainable). It was bad enough that I rewrote the tool later on.

The TL;DR version of what diff-shades does is that it clones a bunch of projects, runs Black on ’em while recording the results. Then you use its other commands to analyze and compare recordings.

Detour: does GCC help?

At this point I had found a workaround to the GCC

array subscript 1 is above array bounds error and was curious to whether using GCC would

produce faster binaries. The answer turned out to be very much no.

Anyway, other than getting distracted by diff-shades, I looked into the gcc issue to find a potential workaround. I found one, but it was useless 🙂 Collecting numbers for both gcc-10 and clang showed that gcc fails in basically all departments:

- takes almost twice as long to compile Black AND definitely uses 200%+ more memory

- had no meaningful difference in generated binary size all while being far more picky about the C code it’s given

- oh and of course produced binaries that were around 8% slower 🙃

I’m honestly happy that GCC failed to compile on that parser setup code, clang (for Linux) is so much better.

Results

Quick note

I also did some micro-optimizations like reordering if checks to hit the common case first or replacingx = x + 1withx += 1, but to this day I don’t know whether they actually had an impact.Additionally, I haven’t discussed the last optimization round I did for src/black, but there’s nothing in that which I haven’t covered yet.

Anyhow, these optimizations bumped the parsing speedup over interpreted from ~1.73x to ~1.9x. You can see the changes made here and also here.

For more detail, see the tables at the bottom for the compiled-mypyc-preopt and

compiled-mypyc columns in this report I compiled. It took a long time to

compile this report by the way, setting up a properly configured benchmark setup and

gathering multiple data samples is very time consuming!

In the end, I managed to increase compiled performance by an additional 10-15% which is pretty nice! I was aiming for 25%, but in hindsight I might have been hoping for too much 🙂. Also yes, they were virtually useless when interpreted.

We’re nearly there, only Pt. 3 - Deployment remains. It’s shorter, believe me.

In the end, I had to revert this optimization so Black wouldn’t crash under PyPy, can’t remember what the error was though ↩︎